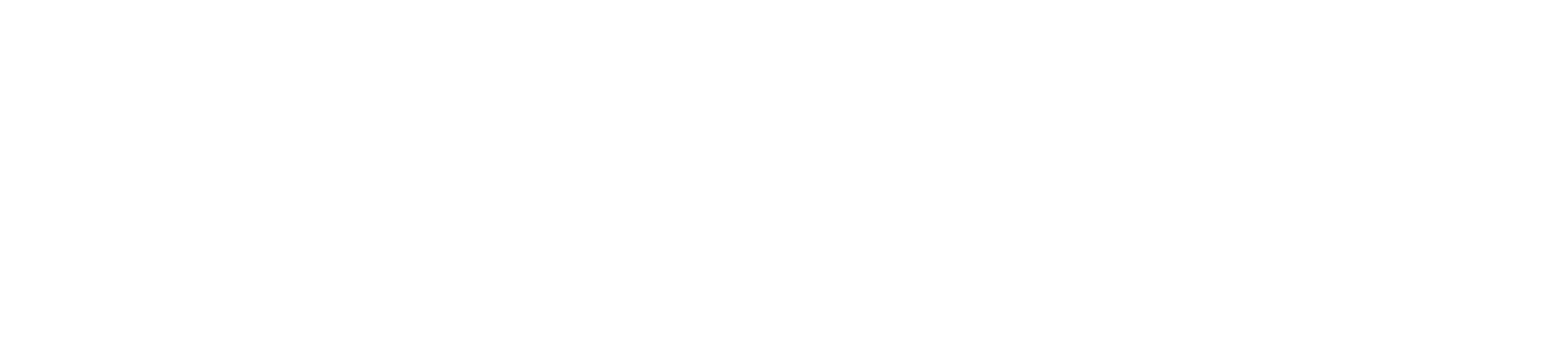

Kristie Goforth: Paulius Musteik

Candidates for Monona mayor 2023: Kristie Goforth and Mary O'Connor

Former city council member Kristie Goforth, left, is challenging Monona Mayor Mary O'Connor.

Monona doesn’t usually see the kind of political storms that roil Madison, its much larger neighbor. But things started heating up in 2021 when some newcomers challenged a perceived “old guard” of incumbents in the mayoral and city council elections. The incumbents, including current Monona Mayor Mary O’Connor, prevailed. But mayoral challenger Kristie Goforth, who served on the Monona city council from 2020-22, is back for another round, running against O’Connor, who is seeking her fourth two-year term.

“There’s three things I’d like to get accomplished — to see finished — before I leave office,” O’Connor tells Isthmus. She wants to complete planning for the San Damiano site, the large lakefront property purchased by the city in 2021; pass a referendum to finance a new public safety facility; and pursue more affordable housing development.

Since state law prevents cities from requiring developers to include affordable housing in their plans, O’Connor has an alternative. “I have worked on putting together what I’m calling a toolkit of various incentives that we could use to encourage at least part of some future developments to be affordable,” says O’Connor. “Things like maybe changing parking requirements or increasing density more than we might normally allow.”

Goforth, the executive director of the nonprofit Free Bikes 4 Kidz and the former executive director of the Monona East Side Business Alliance, points to a handful of issues that contrast her vision with O’Connor’s. The most prominent is the proposed bus route through Monona that would come with the city joining the Madison Metro system, a move which both candidates support.

Goforth, however, does not want the route to travel along Winnequah Road, a narrow road that is part of the Lake Loop bicycle route and lacks sidewalks for pedestrians for long stretches. “Putting the bus in that mix seems quite dangerous in my eyes,” says Goforth. “I’m a cyclist. I’m excited about us joining Metro, I think it’s a great opportunity for us, but we need to be careful in the route we choose.” She would like to see the route stay on or near Monona Drive. She says businesses along Monona Drive that have had trouble staffing are eager to connect with the Metro system so workers can commute from Madison.

For years, Metro buses have passed through Monona without making stops, as Monona found the cost of joining the system prohibitive. This time around, joining the Metro system as part of its system redesign would cost Monona less than it currently pays to maintain its own transit service. The city currently has a survey out to gather public input on potential changes to the bus system.

Budget hurdles

Whoever takes the mayor’s office will be managing these transit issues, big new projects, and a housing crisis, while operating under a state law that makes it tough to raise new revenue.

Despite the state’s record budget surplus, both candidates say that 2024 will be a difficult budget year for Monona. That’s because state law limits the amount of money cities can levy through property taxes each year, an amount tied to the value of new construction. If Monona wants to raise more money to cover operating costs, the city’s only option is to put a referendum on the ballot where voters would need to approve additional spending, something O’Connor considers likely.

“The state levy limit is just not allowing us to meet our operating needs,” says O’Connor. “For 2023, we had a total of $95,000 that we could increase operating spending. And that’s to cover raises for 75 full-time employees. And we’ve got a couple hundred part-timers given the time of year, and health insurance [cost] increases.”

“With levy limits, every city is struggling to meet the increasing costs of inflation,” agrees Goforth. A budget with no levy increase, says Goforth, “is really like a 10% decrease because all the service costs went up.”

O’Connor is already planning a referendum campaign to finance a new public safety facility. “We have had all kinds of problems with HVAC and plumbing. We’ve had to completely replace a bathroom or two because they’re literally falling apart,” O’Connor says of the current facilities. The police station and fire station are currently located in city hall. She says the buildings are reaching the end of their natural life and previous city officials have kicked the can down the road on replacing them.

Addressing racial inequality

A week after the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd in 2020, Monona police responded to a report of a “suspicious person” with their guns drawn; officers entered a home on Arrowhead Drive, and handcuffed a Black man in the living room while searching the house. The man they arrested knew the owner of the home and had permission to be there, and a federal judge later found the officers had violated the Fourth Amendment. The city’s insurer paid out $150,000 to settle a civil rights suit stemming from the incident.

Since then, O’Connor says, the city has made strides in addressing racial disparities. In 2021, the police department hired a Black police chief, Brian Chaney, who O’Connor calls “a breath of fresh air.” People of color have been added to the police force with some help from city funds that have paid for training, and city staff has become more diverse as well. O’Connor also convened an ad hoc work group on diversity and equity issues that produced recommendations about how to make Monona more welcoming to people of diverse backgrounds.

“This stuff doesn’t happen overnight. It takes time,” says O’Connor. “We’ve made some good steps.”

But problems still linger. Goforth, who is biracial and a member of the Sault Tribe of Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians, says she has faced occasional hostility to her Native identity while knocking on doors for her campaign. And some of the city’s issues with diversity — Monona is about 92 percent white — impact other city issues as well, says Goforth. Goforth says the alternate route she is proposing for the Metro bus line on Monona Drive, for instance, would better serve the city’s marginalized communities, while those with homes on Winnequah Road are more affluent and less likely to need or want bus service.

She has also fought a proposed market-rate housing development near her home, The Bloom, which would add housing units to the market, but with many out of reach for the city’s people of color. A one-bedroom at The Bloom will go for about $1,800 a month, according to a rent matrix the developer presented to Monona’s Plan Commission. That rent would be affordable to the average white Monona resident, who, according to Census data, has a household income of about $94,000 a year. But Latino households in the city make about $63,000 on average and Black households just $40,000. Median rent near the development is about $980, according to the most recent American Community Survey data.

The city is currently contemplating subsidizing The Bloom development with about $3 million in tax increment financing and selling a nearby plot of land owned by the city to the developer for $1, though the proposal has been tabled at recent public meetings.

Goforth says she would have liked to see the development focus more on community needs, possibly including a teen center for students of the nearby high school or workforce housing that would be affordable to school staffers. Says Goforth, “It’s a financial win for the city, but it seems like the neighbors aren’t being listened to.”