Keith Furman

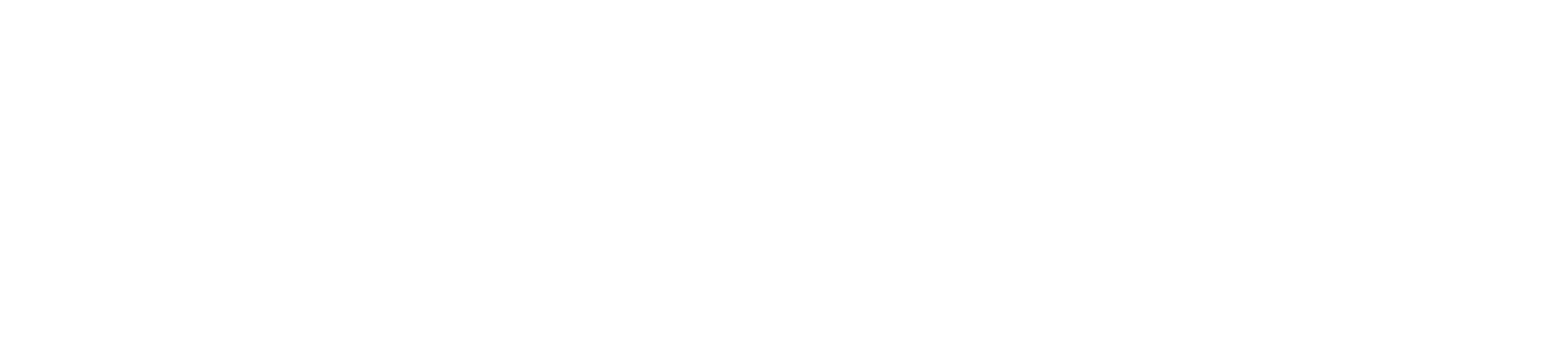

The evening commute on Aug. 20, 2018, proved hellish for some, including those stuck in stalled cars on North High Point Road.

And so, the story begins with a storm of biblical proportions.

August 20, 2018. What you remember about that day depends on where you live, or where your commute takes you. If you were on the west side during the Monday evening rush hour, there’s a chance you were stuck in your stalled car, or trapped inside some local business as flood waters poured in. If you were home east of downtown, you wondered what the big deal was. That is, until you turned on the news, or a couple of days later when lake levels surged upward and the sandbags came out.

If it all seemed familiar, it was because we’d been through something similar two months earlier, when thunderstorms dropped between 3 and 5 inches of rain overnight on June 16, causing widespread flash flooding. By contrast, at the peak of the 11.5-inch (in Middleton) late-summer storm, rain was falling at a rate of 2 to 4 inches per hour.

“That August storm was off-the-charts intense,” says Phil Gaebler, a water resources engineer with the city of Madison. “In June, you had infrastructure that flooded but stayed in place, whereas in August the infrastructure got flooded and washed away. Rarely does that actually happen. It was one of those things that has such a low probability of occurring that it kind of shocks people when it does.”

If that summer’s weather merely shocked residents who hadn’t thought much about storm sewers, it fully got the attention of engineers who had. Almost immediately, metaphor was transformed into reality. That summer really was a watershed in the city’s response to dealing with stormwater in the climate-change era of stronger and more frequent storms.

Along with boosting funding for repairs and flood control projects, the city launched an 18-month study of eight west-side watersheds, topographical areas that determine the direction of stormwater flow from the city’s built environment toward bodies of water such as streams, rivers and lakes. The studies kicked off with a series of informational meetings during the winter of 2019 and continued through more than 30 focus groups with residents of flood-prone areas last fall, as engineers and consultants involved in the studies began building a calibrated hydraulic model that could predict flooding timelines and impacts for storms of differing intensity, identify problem areas and evaluate the performance of existing storm sewer systems. Now, in a second round of public information meetings occurring in March around the city, residents are being given access to engineers’ detailed inundation maps so they can give engineers feedback on flood spots the model is missing, or has inaccurately included. “In general, it’s helping us see whether, in the process of fixing a known flooding problem, we’ve actually made something else worse,” Gaebler says. (While the west side was selected first to take advantage of residents’ fresh catastrophic memories, the city plans to study all of its watersheds, beginning in 2021 with the east side’s main watershed of Starkweather Creek.)

Though they may lack the catchy name given the county’s removal of sediment from Dorn Creek and Token Creek north of Lake Mendota (“Suck the Muck”), the studies even in this early stage have been invaluable to engineers and residents alike.

“Our engineers have gone out into the community and walked some of these areas with residents, and now we’re sharing the information that we’ve gathered so the public can confirm it,” says Hannah Mohelnitzky, public information officer for the city’s engineering division. “We’re also livestreaming this spring’s meetings, because we want to reach as many people as possible. We really want feedback from everybody. We don’t want to design a model and not have it match up to what people are experiencing.”

One of the eight watersheds being studied is Wingra West, 1,778 acres stretching from Lake Wingra all the way past the Beltline to the southeastern reaches of Middleton Township and the western edge of Research Park beyond Whitney Way. Nearly all of that land theoretically channels its stormwater to the lake through a culvert under Nakoma Road, which happens to be located 75 feet from my house. (The other primary outfall is located at Glenway Street.) In fact, the water during the strongest storms courses over Nakoma Road and creates a very popular if intermittent kayak course, which it has done regularly on Manitou Way since I first experienced it in June 2008, the same night that Lake Delton breached County Highway A and emptied into the Wisconsin River.

Ten years later, when stormwater began backing up from my basement’s floor drain and sewage rocketed from the laundry sink during the late afternoon of Aug. 20, it destroyed what had twice been a finished basement. I was lucky in that the damage had not yet been fixed from June’s flood, and way luckier than my neighbors even closer to the culvert, who spent two nightmarish nights that summer on tiptoes, palms pressed against basement windows, in a futile attempt to keep a wall of water from capsizing their house. While FEMA defrayed a small portion of my cost to replace drywall and lost items, all of the fixes intended to prevent a three-peat — cutting into the basement slab to install clapper valves in outgoing pipes, introducing rubber sheeting along buried foundation walls and replacing overwhelmed sump pumps — fell outside the boundaries of homeowners insurance as “improvements” to the property.

During the 2005 purchase, I recall the seller mentioning infrequent basement moisture and dismissing floods as “once a century” events. As the city’s web page devoting to flooding (www.cityofmadison.com/flooding) points out, a 1 percent (100-year) event has a 26 percent chance of occurring during a given 30-year mortgage, and more to the point, this 15-year stretch has now seen two 100-year events and one 1,000-year event. Whether we like it or not, we’re all going to have some role to play in the city’s attempt to tame flooding in Madison.

It might even be a meatier role than we imagine. So says Gaebler, who is overseeing the study of the watershed I live in. Although specific proposals will not be out until later this year at the earliest, the city is sure to embark on a number of public-space solutions, including digging detention basins to slow down the flow of stormwater, upgrading old pipes to new design standards where possible to allow more water to flow through known pinch points in the system, and adding inlets to allow notoriously low spots in intersections to drain even during high-volume storms. The city is close to going out to bid on a pilot study of pervious pavers and precast concrete panels to be used on streets in the Westmorland neighborhood. But officials also want to involve residents in what is sometimes called green infrastructure, “where you’re trying to make the watershed function the way it did before there was development,” Gaebler says. Among the drawbacks is the amount of maintenance green systems require (for example, regular removal of built-up sand and sediment); another is jurisdictional.

“We’ll have detention ponds, we’ll have rain gardens,” he says, “but one of the big asks as we venture into green infrastructure will be to get people to put rain gardens on their personal property. We ask for it now, but if you think about what it will take to reduce the volume of water that flows to our lakes, it’s going to be important to figure out where to place all this volume control infrastructure. It’s hard for a municipality to spend money on private land, and the government structure isn’t set up for it, but private land might be the best spot to do volume control, and we’re looking for ways to incentivize it. We have some work to do to develop that program.”