How new shop owners are remaking the eclectic avenue

“I would say it’s an incredibly accepting neighborhood,” says Paul Hoffmann. “I think it doesn’t matter who you are, what’s your background. If you come in there with good interests and to help out, you’re just accepted.”

American TV, A to Z Rental and Klinke Cleaners got their start there. Most of its businesses are not only locally owned; the owners live nearby. Residents seek out local and buy local, leading to a stunning revitalization. And in this anonymous Internet age, they all know each other.

In almost every way, it is Madison’s Mayberry — if Mayberry boasted revitalized shopping and dining districts.

It is Atwood Avenue.

“The Atwood Avenue area is one of the most exciting places in Madison,” says Mayor Paul Soglin. “Its economic revitalization is a critical component of the success of the east side.”

Hoffmann notes that, despite Atwood’s classic funkiness, “Bankers walking around with suits and ties are as accepted as anyone else.” He’s president of Monona State Bank, which in January opened a branch in the historic Security State Bank building at 1965 Atwood.

“People come in and bring us flowers, even if they’re not doing business with us,” he says. “They make us feel so incredibly welcomed, which I think is a great reflection of that street and that neighborhood. It sums up Atwood.”

The bank is at the intersection with Winnebago Street known as Schenk’s Corners. The area is at the heart of Atwood’s rebirth.

It’s a revitalization that has been ongoing for nearly three decades, but at an accelerated pace for the last five to 10 years. The flood of new establishments — including bars, restaurants, galleries, cafes, even a retail clothing store — can be chalked up to, among other things, careful planning by developers invested in the area, a built-in customer base of residents who like to walk to local food and entertainment options and still relatively affordable real estate with historic character.

Local businesses have helped cultivate the robust feel of the avenue with new music festivals and community celebrations. Stalzy’s Deli, 2701 Atwood, for instance, celebrates its fourth annual Oktoberfest this weekend with a festival featuring eight local bands and traditional German food and beer. In August, Tex Tubb’s Taco Palace, 2009 Atwood, hosted the second annual Atwood City Limits music festival. There is also now a Schenk’s Corners Block Party and a rebranded AtwoodFest that spans two days. Madison Traffic Garden also this summer took advantage of a trial closure of Jackson Street to create a temporary plaza, hosting weekly events featuring food carts and repairs of small appliances and bikes by Atwood Tool Library volunteers.

A key project that sparked the latest round of growth on Atwood is Kennedy Place, Joe Krupp’s sizeable mixed-use development at 2045 Atwood, which opened a decade ago. Its business tenants include Moonsoon Siam, a popular new Thai restaurant; Snap Fitness; and Catalyst, which carries sports clothing and gear.

“This project helped to provide the neighborhood with new people excited to live, shop and dine in their new neighborhood,” says Hoffmann. “When developers are willing to take a chance on a neighborhood by putting up projects of this magnitude, it sends a signal to others that the neighborhood is improving and they should take notice. It can be a big risk, but it was one of the catalysts for regenerative growth in the area.”

Leanne Cordisco, who opened the Chocolaterian Cafe, 2004 Atwood, with business partner Kimberly Vrubley about two years ago, also credits her landlords, Peder Moren and Connie Maxwell, for carefully choosing tenants that complement each other and “capture the spirit of the east side.” Moren and Maxwell own a substantial amount of real estate in Schenk’s Corners.

“They were looking for the right fit to continue this rebirth,” says Cordisco. “Rather than trying to rent out to the first person, they wanted to rent to the right people.”

Krupp himself chalks up the area’s rebirth to a variety of factors, including a shift in values and lifestyles. Ten years ago, he says, “we were coming out of a really bad economy. People were ready to start businesses. I think there’s a new generation that, out of necessity, is a lot more entrepreneurial.”

Meghan Blake-Horst, the former owner of Atwood’s Absolutely Art, which closed on June 28, agrees. “It’s timing,” she says. “I know many of the owners are young professionals, under 40. So 10 years ago they would have been in college and nowhere near ready to start a business.”

Brad Hinkfuss, chair of the Schenk-Atwood-Starkweather-Yahara Neighborhood Association, says the recent entrepreneurial activity is just the latest wave in the street’s ongoing revitalization.

“This isn’t so different from the history of Schenk’s Corners and Atwood Avenue,” he says. “Sometimes I think we’re simply re-creating much of what we lost over the years.”

‘It was a struggle over here’

While Schenk’s Corners is the anchor for the entire street, it’s just part of an overnight business renaissance...that was 25 years in the making.

“It did go through a very bad time when the shopping centers opened, and then East Towne,” says Ann Waidelich, co-leader of the East Side History Club and an encyclopedia of Atwood knowledge. Critics also credit the Eastwood Drive bypass, constructed in the 1970s, with routing business away and making access difficult. The opening of the Beltline in the 1950s didn’t help, either.

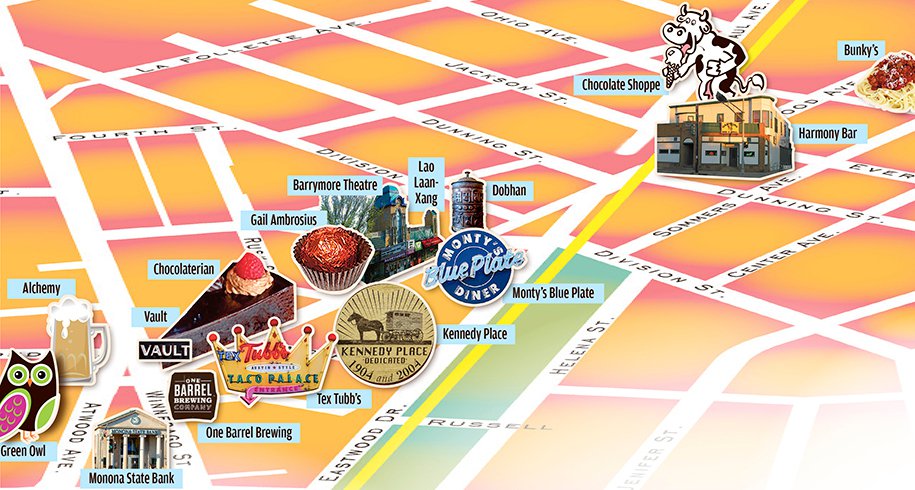

The first step back was when a community fundraising effort succeeded in taking over the Cinema Theater, 2090 Atwood. By the mid-’80s the 1929 movie palace had become a porn theater. It was reborn in 1987 as the Barrymore Theatre.

“I think that the Barrymore was and still is the center of the redevelopment of the neighborhood,” says Steve Sperling, the Barrymore’s manager.

The Barrymore represented a new beginning for the economically depressed street. But it was only a beginning. Many unsung heroes come up in discussions of the greater turn-around. Moren and restaurateur Jane Capito are often mentioned, as is Krupp, owner of Prime Urban Properties. He moved his business to the historic Kennedy Dairy barn in 1985. (Its address today is on the relatively new Eastwood Avenue; historically, it was at 2049½ Atwood.)

“In the late 1980s and early ’90s it was a struggle over here,” says Krupp. “We still had lots of vacant bars. There were a couple of gas stations that were abandoned. It wasn’t a pretty sight.”

A housing development on Amoth Court, the only through-street between Atwood and Eastwood, was his first project. Hoffmann and his wife were among the first tenants.

“I loved that neighborhood,” Hoffmann recalls. “It was starting to come back then, but it was still very early.” Before the housing project it was a parking lot, “an eyesore and a problem, and there was a lot of drug use there.”

With Moren, Krupp helped develop what would become Monty’s Blue Plate Diner at 2089 Atwood, which opened in 1990. Krupp went on to develop nearby Kennedy Place and Kennedy Point Condominiums, and Monty’s owner Monty Schiro went on to become a principal of Food Fight, a consortium of employee-owned restaurants that includes Tex Tubb’s Taco Palace.

“To have that vision and really put that money into the neighborhood,” says Hoffmann of Krupp. “He doesn’t get the credit he deserves.”

“I obviously was looking at the long haul,” Krupp says. “It immediately grabbed my attention that what was surrounding me needed work. So that motivated me to invest, particularly in the immediate adjacent areas.”

There are too many other stories, too many interesting businesses, to describe Atwood in its entirety. But we can get a taste by walking its length from east to west, a little more than two miles.

Like family

The street is named for David Atwood (1815-1889). He served as a general in the Civil War and, afterwards, as Madison’s mayor. He also published what became, after a series of mergers, the Wisconsin State Journal.

There has always been some semblance of Atwood Avenue. Waidelich says it began as a Ho-Chunk Indian trail, leading all the way through Monona.

Atwood’s original landscape is recalled in the name of a township that split off in 1850, starting at the Yahara River. James Kavanaugh, an early town of Madison clerk, wrote in 1877 that the new town of Blooming Grove was named for prairies “full of wild flowers in great abundance, of the most beautiful colors imaginable.” For at least a half century, all developed land was used only for farming.

Atwood begins at First Street and ends at Monona Drive and Cottage Grove Road. Even at its easternmost edge, the avenue’s sense of community is pervasive.

“We have people who have come here for the 19 years we’ve been open,” says Kristin Hanson, manager of the Walgreens at the intersection of Atwood and Cottage Grove Road. “One of my pharmacists lives in McFarland. He told his wife he doesn’t want to leave here because these customers have become like family to him.”

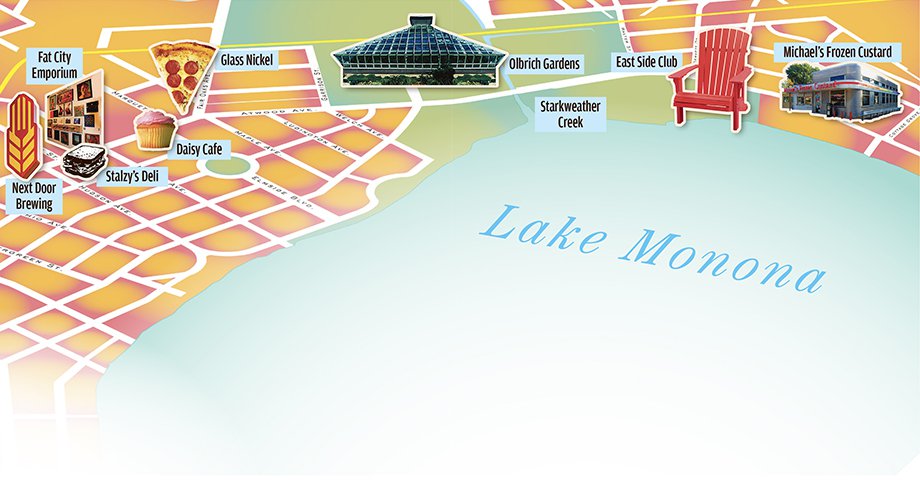

Michael’s Frozen Custard, 3826 Atwood, opened in 1989. “We chose the Atwood neighborhood because it had many great things to offer,” particularly the spirit of its residents, says owner Michael Dix. “Creating great communities starts with neighbors supporting local businesses.”

Across the street is the East Side Club, formerly the East Side Business Men’s Club, which has capitalized on the new blood in the area by increasing its food, entertainment and catering options. As one of the few public watering holes in Madison with ample lake access and beautiful views of the downtown skyline, the club draws large crowds to its summer Tiki Bar and Sunset Music Series.

Olbrich Park and its botanical gardens at 3330 Atwood were conceived by Madison attorney Michael Olbrich in 1916. He purchased the land and had a design created by the architect for the Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association. He was also instrumental in the creation of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum. In poor health and facing financial problems, Olbrich committed suicide at the age of 48, just before the 1929 Wall Street crash.

Great synergy

Atwood’s business district begins in earnest west of Fair Oaks Avenue.

The five-year-old Daisy Cafe and Cupcakery, 2827 Atwood, was at one time a strip club, according to Kathy Brooks, who owns it with her husband, Daryl Sisson. “I’ve been living in the neighborhood for 30 years,” she says. “I love it here.”

Glass Nickel Pizza, 2916 Atwood, and Bunky’s Cafe, 2425 Atwood, are already Atwood institutions, joining the Harmony Bar and Grill, 2201 Atwood, which opened in 1938 as Vic’s Bar. Brad Czacher, a former employee of the bar, bought the Harmony a year ago. With live music, he sees business from across the city and out of town.

Patrick Downey opened the Victory at 2710 Atwood in 2010. Its tiny Brooklyn predecessor had earned notice from The New York Times and New York Magazine. The Madison cafe made news in 2011 when a rock was thrown through the window, just above a sign calling for the recall of Gov. Scott Walker.

Next Door Brewing Company, 2439 Atwood, opened a little more than a year ago. “All of the local businesses have been very supportive right from the start,” says Pepper Stebbins, one of the partners. “We make a point to visit these businesses, and they in return visit ours. It’s great synergy.”

Absolutely Art at 2322 Atwood had been a neighborhood favorite, but Blake-Horst closed shop because of problems with the building, not for lack of loyal clientele. She says she was especially touched when middle-schoolers and teenagers who had been coming to the store since they were babies stopped in to say their farewells.

“They were just in tears,” says Blake-Horst, who continues to live and work in the neighborhood, now at Safe Communities, 2453 Atwood. “To see students reacting that way — it talks about how they’re raised and how they’re influenced by local business.”

Fat City Emporium, a gallery that features arts and a gift shop, is helping fill the void at 2716 Atwood.

Blake-Horst says the bike path out her back door was critical to her store’s success, just as it is now for Chocolate Shoppe Ice Cream. Company vice president Dave Deadman, who has lived in the neighborhood for 20 years, says he has long had his eye on the little corner building at 2302 Atwood. “With the increased popularity of Atwood Avenue for restaurants and bars, I thought it was a great time,” says Deadman. The shop opened May 2 and immediately took off, with lines of customers a common sight on warm summer nights.

Deadman also put in a landscaped backyard patio with benches and chairs. This, too, quickly became a popular gathering spot for residents.

Just to the east are popular dining spots Dobhan, 2110 Atwood, which features Nepali and Tibetan dishes, and Lao Laan-Xang, 2098 Atwood, which specializes in Laotian cuisine.

How long has the genuine, old-fashioned Atwood Family Barber Shop been at 2140? “Oh, I don’t know, 70 years?” says Terry Moss, looking up from a client’s shaved head. He’s worked there for almost five years and owned it for more than a year. A haircut is $15.

Schenk’s Corners

Gail Ambrosius Chocolatier is located at 2086 Atwood for a simple reason. “I just wanted to stay in the neighborhood. It’s a great location,” says its eponymous owner — and yes, that’s her real name.

But that doesn’t mean Ambrosius is homebound. “We get our chocolate from Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Hawaii. I just returned from Costa Rica and I got some beans from the farmers I’ve been working with.”

Which brings us back to Schenk’s Corners or, as the Schenks themselves call it, Schenk’s Corner. It is the street’s reason for being, and the east side’s first shopping district. At the tip of the triangular block, 2000 Atwood, is Vault, an interior design firm offering furniture, accessories and gifts that opened in 2013. At one time it was a Rennebohm Drug Store. The location was very different in 1892, when Fred and Wilhelmina Schenk opened the first business east of the Yahara.

“It started as a tavern, and they lived upstairs,” says Sue Retzlaff, a retired Lands’ End employee who lives in Mount Horeb. She’s the Schenks’ great-granddaughter.

Over decades the crossroads grew to include more family members and more of their businesses, including an inn, dance hall, lumberyard, livery, a department store and, finally, the Schenk-Huegel store, which specialized in durable clothing, particularly for police and other public employees.

It closed in 2011, right before Retzlaff helped produce a DVD with documentary filmmaker Gretta Wing Miller, outlining the corner’s history. Today the store is home to the Chocolaterian Cafe, which specializes in desserts, chocolate treats and light meals.

Across the street is Tex Tubb’s and One Barrel Brewing Company, 2001 Atwood, which touts itself as Madison’s “first and only Nano-Brewery Company.” Launched in 2012, One Barrel is true to its name: brewing beers one barrel at a time and serving them for limited periods.

The Green Owl Cafe, 1970 Atwood, opened in 2009. It remains the city’s only dedicated vegetarian restaurant. And the opening of Alchemy Cafe at 1980 Atwood in 2008 helped appease those who were mourning the closing of Wonder’s Pub in the same location.

As for the future of the area, Hinkfuss says the planned reconstruction of Atwood Avenue and Schenk’s Corners is “the biggest thing on the horizon. “The Corners will come first in 2016, with most of Atwood Avenue to follow around 2020,” he says.

A corridor planning effort is also under way. “It’s the idea of taking our public spaces — streets, right-of-ways, terraces — and redesigning them to foster better business environments and more engaging pedestrian places,” adds Hinkfuss.

But things seem to be working pretty well as they are. Says Chocolaterian’s Cordisco of activity around her shop, “On weekends it’s alive from 9 in the morning to 2 a.m.”

— Paul Hoffman, Monona Bank president

10 years ago they would have been in college"

— Meghan Blake-Horst, former owner, Absolutely Art