Eric Tadsen

Walk up Wisconsin Avenue toward the Kennedy Manor Apartments on a summer day, and you're likely to find Fred Mohs - wearing carefully creased jeans - trimming the hedges.

Yes, that Fred Mohs - the lawyer, former UW Regent, real estate developer, iconic downtown supporter, and board member of MGE, the Madison Symphony and Downtown Madison Inc. He owns 60% of the block, including his house on Wisconsin Avenue and, most importantly, Kennedy Manor, the historic apartment building at 1 Langdon St.

"Nobody can do it as well as I can," asserts Mohs, who has been trimming hedges since he was 12. "I'm perfect. I am a fabulous hedge trimmer and gardener in all respects."

Mohs adds with a laugh: "Seriously, I have 58 years' experience in mowing."

Welcome to Fred Mohs' world, where the hedges are trimmed perfectly, the walks are shoveled almost before the snow stops falling, and Mohs carefully tends his collection of antique buildings, creating a neighborhood where Mr. Rogers would feel at home.

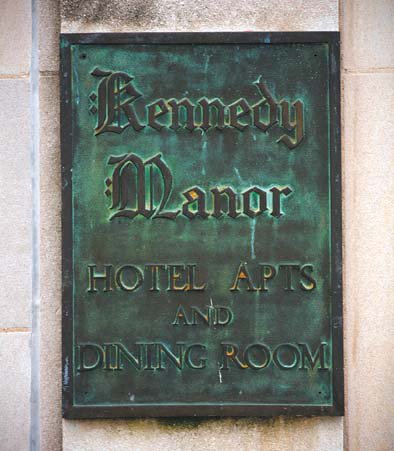

Kennedy Manor is a throwback of sorts to a different time and place. The terrazzo floor, the brass elevator doors, the light fixtures - all look the way they did in 1929, when the building was built. Residents can still order room service or pop downstairs for dinner in the basement restaurant. There's still every-other-week room cleaning, included with the rent.

Mohs pampers the building, which he calls "my pet," and relishes the community he's created. The people who live here and animate the building are a huge part of the charm. They look out for each other, as good neighbors do.

Mohs, now 70, didn't set out to make Kennedy Manor a social experiment or living museum piece. Yet his efforts to preserve it have been nothing if not deliberate. "I did it for social reasons," he says. "To change the character. To change the social patterns on the block, to make people more considerate of one another, which has worked incredibly well."

For instance, he's refused to convert Kennedy Manor to condos in part because he'd rather be a real landlord than leave a condo association in charge.

The 58-unit apartment building is still heated with the original, massive Kewaunee boiler, attended to by building manager Steve Kjin and maintenance man Doug Anderson. "If Steve and Doug and I can keep that thing going until 2029," says Mohs, "we're going to have a celebration in the boiler room."

Weighty doors, Chicago faucets, original locks that would cost $500 each to replace are all still here. The elevator's original brass doors are polished every Friday. Original light fixtures still shine.

"Everything was the finest," boasts Mohs.

The building's tenants - a diverse, often quirky bunch - routinely stay until they die or can no longer live alone. Louise Marston, a longtime society columnist for the Wisconsin State Journal, lived here for almost 70 years. Another lifelong resident, Magnus Swenson Harding, was a Norwegian American Steamship Company heir who worked on the Manhattan Project. Marcy Starks, the building's first African American tenant, helped promote American Girl's Addy doll. Ted Kouba, who worked at the U.S. Forest Products Lab in Madison, had an archeological site named after him.

Kennedy Manor's denizens love the way Mohs pampers them and the building. "Fred's not uppity," says a 47-year resident who doesn't want to be named. "But he likes his place perfect."

Mohs agrees. "I am not going to let it go the way a lot of other old buildings go," he says of Kennedy Manor. "These buildings must be maintained."

He pauses, realizing there's more to the story.

"That isn't why I do it. It started long before that."

In the late 1920s, dentists and brothers Tom and Grover Kennedy owned eight downtown buildings and 2,000 acres north of Lake Mendota. But they had not built anything and, says Mohs, "They wanted to build a monumental building to honor their family."

The brothers' timing was dismal: Around the time the building was completed, the stock market crashed. The Kennedys hung on, opening the five-and-a-half-story building, including the Kennedy Manor Dining Room and Bar in the basement. Nora Peterson, who ran the restaurant for decades, later told the Wisconsin State Journal that "the cream of the city lived at the Manor" in the 1930s.

Kennedy Manor's inaugural tenants included business managers, a company president, a UW associate professor and, of course, their wives. The building also housed a surprising number of single women renters, including two department store managers, the State Board of Health's director of nursing education, an insurance counselor, two physicians, an osteopath, a nurse, the Postmaster's secretary, an interior decorator, the Board of Education's attendance supervisor and the Board of Vocational Education's home economics supervisor.

These were the days when housecleaning was done by maids, and dirty linens were laundered. You could dance on the roof. Minuscule kitchens were barely needed with the downstairs restaurant, known for fine foods and cocktails in a refined atmosphere.

Even today, Dawn and Mike Thiesen, who run the Kennedy Manor Dining Room and Bar, feel more like caretakers than proprietors. They've inherited the vintage brass lamps, maroon and gray-banded Syracuse china, original chairs and pressed glassware. They'll pass them to the next owners when they leave.

When the couple bought the business and began leasing the space on Dec. 31, 1999, Mohs laid down two rules: no noise, no garbage. When it came time to renew, Mike Thiesen remembers Mohs saying, "You followed the rules. You can stay as long as you want."

These days, some tenants still eat here or order room service. Couples who had their wedding breakfast at the Kennedy return for anniversary celebrations. Regulars make up a large share of the restaurant's clientele.

"It's kind of like a big family," says Thiesen. "We want to have our clients feel like they're part of our family too."

Jim Draeger, deputy state historic preservation manager, notes that luxury apartments like Kennedy Manor emerged first in New York City, born of a growing upper middle class. "This was a way people expressed their wealth and their status," he says. "Kennedy Manor tells us something about who people were and how they lived."

These apartments, like condominiums today, filled a niche for people who did want to take care of a house and yard. "There are not new ideas," Draeger notes. "Historic buildings let us keep the old ideas around and learn from them."

Madison boomed in the early 1900s, and downtown land was scarce, says Kitty Rankin, city preservation planner. Luxury apartments provided an option for those who didn't want to move to Maple Bluff or Nakoma.

Kennedy Manor joined apartments like the Ambassador, the Dowling and the pre-World War I Bellevue, which was the largest and most luxurious of its era, Rankin says. But Kennedy Manor is in a class of its own because of its size, its clientele (full-time residents, not students), and the fact that it has been so well cared for.

In 1961, Mohs was 23, just out of the Army, back in law school and buying apartments. His father, a physician, was treating the aging Kennedy brothers, and Grover Kennedy asked young Fred if he wanted to see Kennedy Manor.

Mohs and his wife, Mary, could not afford the rent in the two buildings they owned, but they had investment money and took out loans to raise the $30,000 they needed to buy the $550,000 Kennedy Manor. "This was the most magnificent building in town," Mohs says. "It was astonishing to me to end up owning it."

The apartments came with one full-time employee for every eight apartments, including three maids and a laundress who made soap from the restaurant grease and did laundry for the building's tenants in a wringer/washer. Lillian Kennedy, a Kennedy sister, managed the Manor - "and knew every boo that took place in the building," Mohs says.

The Mohses moved in, joining an impressive enclave of Maple Bluff and Sherman Avenue dowagers. They included Mrs. (Mohs calls them all "Mrs.") Jessie Manchester, widow of Henry and vice president of Harry S. Manchester; Mrs. Ethel Jackman, widow of Ralph, an attorney; Mrs. Lucille Jackson, a widow connected to the Jackson Clinic; and Mrs. Kathryn Smith, widow of Harrison, from Wisconsin Power. They played bridge on Fridays and sent their laundry out because they didn't like the smell of the apartment's soap, Mohs says.

When Mohs bought Kennedy Manor, a friend of his father predicted it would lead to his financial ruin. At that time, apartments were considered a risky venture.

But in fact, it proved to be a wise investment. By the time Mohs was out of law school, his real estate holdings were paying well enough to let him and Mary travel around the world for four months. Within a few years, he and Nate Brand had built the 280-unit Carolina Apartments and the 303-unit Normandy in Madison and the Commodore Club condominiums in Key Biscayne. He and Brand still own the Carolina; another partner has the Normandy.

Liz Allen, hospital chaplain, outdoor lover and "change-the-world junkie," gives guests the best seat on her comfortable sofa overlooking Lake Mendota. The views from Kennedy Manor's lakeside apartments on the third, fourth and fifth floors are to die for - or to wait for, moving apartment by apartment until you get the one you want.

On snowy days, it feels like being in a snow globe, safe in a bubble. In summer, when the windows are open, it seems as though the rooms extend beyond their windows into the view. And, Allen says, "the sun streams like an orange carpet as it sets."

Allen produces a postcard, taken by fellow Kennedy Manor resident Dick Baker, of the sun setting beyond Picnic Point.

"Typically, I would be there in the summer with red on the wall," Allen says. "Or right here." She gestures to a futon. "This is my bed." She uses the real bedroom as an office, and for guests.

That's how things seem to be at Kennedy Manor. Residents fall in love with the building and the view of the lake. They're downtown junkies and university users who've landed at the intersection of city and college life. They embrace small spaces, adopt any adjoining outdoor space as their yard and walk almost everywhere.

"The building is clearly loved," says Susanne Voeltz, who's been here 25 years (see sidebar). "We don't have [dish]washers in the apartments but we have brass polished every day in the elevators. So hey, choose your vices."

Mohs doesn't tear out what doesn't work; he fixes it.

Plaster crown moldings are repaired when they crumble. Paned windows are scraped before they're repainted. The rooms are repainted frequently, not just when new tenants move in.

Unlike most new apartments, Kennedy Manor has concrete floors that muffle sound between floors. The elevator's leveling system was updated 15 years ago, but the folding cage doors must still be opened and closed to go up or down. The bathrooms have a drinking-water faucet connected to hard water, not soft.

"It's nice to have someone care about the place you live in," says Chelcy Bowles, who's been here 14 years. The elegant apartment - antiques, leather furniture and carefully edited art - feels so much like home that she and her husband, Bill Peden, paid to install the hardwood floor in the dining room.

Bowles, the UW's director of continuing music education, plays folk harp and directs Madison's Early Music Festival. Peden, an engineer, plays uilleann pipes.

After eight years, the thought of living forever in a one-bedroom was claustrophobic, and the couple snagged an adjoining unit. Their enviable master suite now fills the main living area of this second apartment.

Wit Ylitalo, a former teacher with four daughters, all teachers, has never been lonely in the 11 years she's lived here. An 80-something Bohemian, she discovered the building while delivering Meals on Wheels and moved in after the death of her pediatrician husband. Some people pay a fortune for big, fancy condos, Ylitalo says, "and they don't have half of what I have."

When Ylitalo left her University Heights home of 50 years, she took the things she wanted - "mainly books and bells, not what you'd call practical." She sits under a disco ball - a switch on the wall sets it spinning - and plays her baby grand piano every day, usually ballads. A cowbell collection hangs from a lattice on the dining room ceiling.

The grapefruit tree between the corner windows is 25 years old. "It won't have grapefruit," Ylitalo says. "It takes two to tango."

Yet for Ylitalo, the thing that most binds her to Kennedy Manor is the people. She says the building reminds her of a radio program, Grand Hotel, that she listened to in college.

"They are diverse," Mohs says of his tenants, calling them "a genteel collection of real individuals, and that's kind of the way it's always been."

Kennedy Manor is the kind of place where people linger and stories survive. Mohs, only the building's second owner, can tell quite a few.

There was the morning, Mohs says, when Louise Marston, still in her bathrobe and slippers, came into the apartment office, saying, "Reverie, reverie. I woke up to the clock radio and they were playing Bill's and my song." Bill was Bill Conklin, who had danced her onto the balcony when she was a girl and kissed her.

They couldn't marry across the Catholic/Protestant chasm, but Conklin returned to Madison after his wife died. "He took one look at her, and she was the young girl he'd waltzed onto the terrace," Mohs says. The pair were married for three years, until his death in 1989.

A widow spotted kissing a handsome Irish contractor in the apartment doorway was not so lucky. "She was shunned by all the other women in the building," Mohs says. "They couldn't talk to her because she'd had this affair, apparently, with this contractor."

The first Jewish tenant "was darling, had the great clothes, the cute hats," Mohs says, "but it was an issue." Business law professor Harry Schuck would stop every morning before he walked to campus to tell Lillian Kennedy: "I believe I will have my car in the circle at 6 o'clock. Good morning, Miss Kennedy." And off he'd walk, Mohs says, returning for a cocktail downstairs before he drove to the University Club for dinner, returned to grade papers, and, at 10, went back downstairs for a nightcap.

During her last years, Jessica Burleigh, who dressed in Isadora Duncan-inspired white gauze, went blind. She'd lie in bed, listen to WHA, call Mohs' mother, who was manager for a few years, and tell her all the things she was grateful for. "You can learn a lot from these people," Mohs says.

Today's residents are creating new stories.

Dick Baker is a photographer, sailor and philosopher, delighted to be in a building he says houses no one normal. He washes dishes once a week in a kitchen not much larger than a boat's galley and repeats dinners of instant mashed potatoes, frozen mixed vegetables, a little chopped chicken, sometimes fish. He moves a table to open up the Murphy bed he sleeps on and works at two computers, one for video editing, the other for photos.

Don't forget the windows. The moon rises, he says, "in a grand arc across the Capitol at night."

Baker moved from East Gilman Street in 1986 because he didn't like walking up the hill to get to his boat at the Union. "I thought if I just lived at the top of the hill, things would be easier for me," he says. He is well known for his willingness to help anyone in need and is rewarded in cookies.

Allen, who moved to Kennedy Manor in 1987, originally didn't like the idea of having maid service. But since not taking it would not lower her rent, she went along. Now it's one of the things that binds her to the building.

"Since I have lived here, I feel as if my mother is still alive. I am so taken care of," she says. "I have lived a different life.... This is a sacred space for me."

Downtown Madison has shaped and held a good share of Fred Mohs' life story. He grew up in Shorewood Hills - "smug, boring and self-satisfied" - but his grandparents lived downtown. His mother loved it.

Ledell Zellers, president of Capitol Neighborhoods Inc., credits Mohs for remaining downtown, as others left. "He's committed to making this a good place," she says, adding his care for Kennedy Manor and its tenants in turn attracts good tenants who stay and also take care of the building.

Mohs' ties are emotional. "I pick up paper on the street," he says. "I tear down posters on the street light poles. I'm getting to be an old curmudgeon."

While he treasures his neighborhood, Mohs admits he wouldn't be so interested if he didn't live there. "I wouldn't have understood the opportunities or the potential problems."

And so Mohs preserves his buildings and finds tenants who understand that playing music too loudly can lead to chaos. He wants to make them more considerate of each other, telling them what's expected of them and what they can expect.

"Our promise is to give good neighbors to good neighbors," says Mohs. "And they appreciate it."

The Kennedy Manor File

What: Kennedy Manor Apartments

Where: 1 Langdon St.

When: Built in 1929.

By: Architects Flad and Moulton. They also designed Ann Emery Hall and Langdon Hall. Flad became Flad & Associates.

Style: Neoclassical. Cream brick with stone architectural elements and a parapet roof.

Building materials: Concrete and steel

Number of apartments: 58. Originally, there were a few hotel rooms on each floor. Today, a handful of the rooms with adjoining bathrooms remain; they rent by the month, mostly to legislators, for $400.

Top rents: $150 a month in 1961; about $1,200 today.

Small is beautiful

The lights are low on a winter night and the inverted pyramid under the Portuguese marble dining room table glows. Susanne Voeltz and James McFadden have transformed this fifth-floor apartment at Kennedy Manor into a cozy home for their family of three.

Their teenage daughter, Nathalie Yahara, grew up like Eloise at the Plaza, a child of the building and the city.

McFadden, the architect who renovated Machinery Row, designed the table's glowing underside. The 9-by-9-foot trapezoid seats a dozen people, with no one's back to the lake. On the end wall, a triptych - ceiling high, nine inches deep - recalls medieval altars.

Carefully chosen dishes are stacked on the marble peninsula McFadden designed between the dining room and a sliver of kitchen. Colorful stemware tops a portable bar cart. The stairway to heaven - a series of McFadden-designed discs with gold-leafed supports - runs up a living room wall for books and art.

"Everything is used; everything is out," says Voeltz, a local publicity maven, arts booster, and former head of Downtown Madison Inc. "We really like the idea of being surrounded by beautiful art, by interesting things, by inspired design."

McFadden says the apartment has never felt small, but living in Kennedy Manor is about making intelligent use of space. The wine cellar is under the bed. The kitchen counter has room for an espresso machine, but no microwave. It's okay. Voeltz doesn't know how to use one anyway. There is room for Nathalie's friends, and a fat Christmas tree. Parties are standing-room-only events.

"We all run into each others' lives on a fairly consistent basis," Voeltz says. She sees this as a benefit.