Madison Museum of Contemporary Art

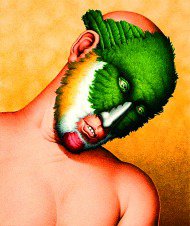

Robert Lostutter's Puerto Rican Tody contains elements of realism and surrealism.

While many of Robert Lostutter's paintings are tense and inscrutable, the artist himself seems anything but. During a gallery talk last Friday to coincide with the opening of his solo exhibition at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, the Chicago artist was affable and wore his emotions on his sleeve.

Lostutter, now in his 70s, welled up with emotion when describing the support of his grandmothers during his youth in Kansas. His paternal grandmother raised him and funded his art-school education. Tears came to his eyes as he recalled how his other grandmother, who had little money, taught him how to draw, supplying him with Big Chief tablets and drawing rabbit after rabbit with him.

Since the rest of his family was not supportive of his interest in art, it's lucky that these two women offered encouragement -- both for his sake and for ours, given the singular and compelling vision on display in The Singing Bird Room of Robert Lostutter, which runs through Jan. 6.

The show is drawn from the museum's significant holdings of Lostutter's work, donated by area art collector and retired UW bacteriology professor Bill McClain. While a few of these pieces were shown in last year's Chicago School: Imagists in Context, this is the first time MMoCA has devoted an entire show to Lostutter.

The artist is known mainly for highly charged depictions of hybrid bird-men and orchid-men. There's an element of surrealism in his work, but also such a meticulousness and realism that these creatures seem plausible. While Lostutter works primarily in watercolor, the show also features oil paintings, pencil drawings and a couple of prints. Impeccable draftsmanship mixes with a penchant for brilliant color.

The 1981 painting Quetzal is a good example of Lostutter's M.O. We see, from the shoulders up, a lone bird-man with brilliant green and crimson plumage. Two long feathers extend back from his head, a bit like antelope horns. His lips are parted, teeth exposed, but his expression is difficult to read: just like a bird with monocular vision, he regards us with one wary eye in a slight backward glance. While the plumage covering his face and head is painstakingly rendered, the human musculature of his neck and chest is stylized.

Other pictures are even more unsettling, as figures are bound with rope, sometimes around their torsos or binding orchids to their faces. Lostutter's interest in exotic plants and plumage was furthered by a trip to Mexico in 1974. He's returned there many times over the decades.

There is a strangeness to Lostutter's work that makes it hard to penetrate -- it can feel like being on the outside of a very personal vision -- but that is also its magnetic pull. Lostutter's memorable work is the result of discipline and skill in the service of a lush imagination.